Breaking Down the Future of Music and AI with Lawyer Ash Kernen

IP and Entertainment lawyer Ash Kernen sits down with Mega Labs to talk about the big issues facing the music industry in the wake of the new AI revolution. We cover the legal battles–including arguments around copyright, name and likeness, right to publicity, and fair use–in addition to "prompt superstars", AI record labels, new revenue streams, and where to find new opportunities in the wake of industry transformation. You can connect with Ash on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Hi everyone,

After a brief hiatus, we're back with a new article we hope will have been worth the wait. We're thrilled to present an in-depth interview on the future of music and AI with IP and Entertainment lawyer Ash Kernen. Ash is a long-time friend and fellow explorer of the tech and music frontier. He's a well-respected voice at the nexus of IP, entertainment and law, working with a number of brands in web3 in addition to his work as a music lawyer.

When the fake Drake x The Weeknd AI-generated viral hit "Heart On My Sleeve" took the music industry by storm a few months back, I decided to call Ash to try and make sense of it all. Below you'll find an edited transcript of that interview.

We explore the legal ramifications of AI-generated music, how record deals and royalty streams might change, how the overall industry will adapt and where new opportunities for artists and music companies might be found. Fair warning, this is a long conversation and there's a fair bit of legal jargon, but it's worth taking the time to go through it all. I left our chat feeling like I had a much better grasp of where things stand on the music and AI front. I hope you do to.

If you enjoyed this and want to see us do more interviews, please reach out at justin@mega-labs.io. We'd love to hear from you. Until next time.

INTERVIEW

So we're going to talk about the legal side of things today, but before we get into all that, why don't you set the stage a bit? What should we make of this whole AI thing?

So here's my theory. I think that ultimately we are going to have a bifurcated media content world. At one end of the spectrum, you'll have the purists. The human-driven, qualitative, personality-ascribed media world that is very much the sort of farm-to-table movement of music. At the other end of the spectrum, you're going to have the purely AI-driven McDonalds of music where it's sort of mass-commoditized and middle-of-the-aisle. And then, there will be all kinds of variations in between.

You will ultimately get new superstars in that world. But interestingly enough, unlike the creators we traditionally think of, these new AI superstars may actually be more the "A&R types" of the world in a lot of ways. I mean, sure they could be producers, but they'll be more “thinking into existence” songs than they would be creating them. And it's the idea that they would be sort of prompt engineers, “prompt superstars,” in a lot of ways. But it’s their ear and their ideas that will be the magnetism to it all.

But here's the thing, at the end of the day, the average music consumer–not everybody, you'll still have your audiophiles and the sort of farm-to-table music people–but the average listener, they just don't care how music is made. All they care about is the consumptive value of music. So if it slaps, it fucking slaps.

As much as creators and musicians want to sit around and fight inevitability, I think that the market is going to ultimately accept and embrace AI-driven music in many, many ways. And anecdotally, the other day I went down a YouTube rabbit hole and started listening to some incredible AI covers. And one of them was Chester Bennington doing an acoustic version of an Audioslave song. And it was fucking incredible. Like it was incredible. I was like, I could listen to this over and over again.

And then I started thinking about all the posthumous collaborations that could happen, right? How many times have we seen a Biggie post-mortem album or record where somebody used an old recording and mashed it up with a new instrumental or something like that? And I'm like, yeah, this is that on like fucking ultra steroids, right? That’s what ultimately is going to happen.

How does the music industry ultimately react to this?

I think it's incumbent upon the industry to get this one right. Because there was an absolute PR nightmare for a long time in the industry [after Napster]. And rather than sort of embracing it and doing what they ultimately did, which is leaning in and monetizing it through streaming, they fought it.

Right now, the way I'm reading a lot of these–and I actually went back and looked at my old deals–they have no real claim to the impression of that artist's voice. They have a claim to the actual use of that artist's voice, but AI modeling is certainly not that.

Now, the interesting conundrum that I see happening–and I have not had a new record deal come across my desk in the last few weeks since this thing really exploded, but I almost guarantee the next one I see that's fresh, their counsel is going to write in there, “Hey, this covers your voice and any sound recording pretending to be.” So, in other words, it's the artist's vocal likeness–not just the actual recording of their voice–that will now be covered under their record deal, meaning that the record label has the right to use an impression of the artist's voice, whether real or simulated through an AI model.

So it's interesting because it's really going to be up to the artist to align with the label to enforce those rights [over their vocal likeness]. But right now, a smart and savvy artist who's unrecouped, might be like, “Fuck you, I'm licensing my voice here. Not you. Tell me where I can't do this under my agreement,” you know?

Savvy artists may actually lean into this. They'll train a contained language model on their own catalog, and then sell that as a plug-in the way you would if you had Craig Lord-Alge plugins or something like that.

That being said, I think the labels are going to do what they typically do. They're going to try to fight it. They're going to figure out a way to slow the train down until they can control and monetize it. I don't know what kind of luck they're going to have with that, but we'll see.

What about artists? Isn't AI just going to take away their jobs?

Of all the arguments against AI, the one that really falls flat on me, is that it's going to dissuade artists from creating. My opinion is, if it's in you, it's in you. There's no amount of infringement, appropriation, or whatever that will stop you.

Look, I don't think it's a panacea either. It's not going to save the industry, and I don't think it's going to destroy it. I think there's going to be a new balance, and it's going to be another sort of vertical we have to incorporate into the overall picture. And there's going to be some really, really interesting uses of this technology.

Like there's also an entire conversation around the creator side of it, using it as either fire starters in the lab and sort of spurring off ideas, or making new sort of instrumentation and sounds using AI.

So I think there's pros and cons on both sides. It's exciting, and again, putting all the legalities aside, I do think it's a double-edged sword. Here's what I mean by that. It's going to only make the creation of music that much more easy, and if we thought we had a volume problem before, it's only going to be bigger moving forward.

So yeah, that's the high-level analysis of a bifurcated market where you have one end like a total AI-driven, mass commoditized, inorganic, high fructose corn syrup, middle-of-the-aisle music. And then at the other end, you'll have this sort of organicism still intact. That's sort of the way I see it, and I think in some ironic way, this mass commoditization of music creation is actually going to spur on and bring value and demand to the craft music movement.

Right, right. That point about bifurcation is super interesting because it sort of applies to almost everything in terms of media and the internet and technology and all that. It's like either TikTok, or super long in-depth TV series that span multiple seasons. Or it's Twitter, and Substack. But it's no longer the generic local news kind of thing.

And so you making those comments makes me think a little bit of that. It's like, you can think of an idea and have a song out in 30 seconds or you can really focus and have that kind of craftsman, handcrafted, authentic, straight-from-the-farm, music. Straight from the creator.

There's a few different ways that we can go from here. Maybe let's just start with the legal side of things because I think that is probably the biggest piece of the conversation right now.

Before we jump into that, let me just say one last point on that prior thing, which I didn't touch on, which is that there will also be labels who actually bypass the human artist. Like completely.

So think about the amount of capital it takes to break a human artist. It can be anywhere from dozens of thousands of dollars to millions for serious players. That's a heavy commitment without a guarantee the label will even like the records the artist comes back with. But with AI, you could create dozens of demo records in a fraction of the time and money it would take to create five or six records by a human artist. So there will literally be labels that just exist to either create AI-driven music in-house or through prompt engineers, and the costs associated with that will be exponentially smaller. Or I should say the risk-to-reward and the hit-to-dud ratio will be less meaningful.

So when some artists talk about being supplanted by AI, it's not a totally crazy idea that should be dismissed. I should add here, our old paradigm is going to get rocked.

That's for sure. Okay, so let's talk about the legal issues.

There are none. I don't know what you're talking about.

Haha right. Yeah, we've got it all figured out.

The main ones that seem to come up are copyright, and then name and likeness, and publicity. Maybe let's start with those.

Are these AI-generated songs breaching copyright?

So I hate to say it, but as a lawyer, so much of it depends on the specific facts at hand. And let me tell you why. You have two areas of focus at the moment around the copyright question: the input and the output. And along with that, we have two different stages of consideration at the input level.

So the first group of people who are angry about the use of their music in AI models are focused on the learning, i.e. on the ingestion and training portion.

It is their contention that, quite literally, you have to make copies of their music to train your model. And it's at that moment where you make additional copies that you are violating the right of reproduction.

Conversely, there are counter-arguments that say, “Oh, you don't understand the technical process. We're never actually making copies.” Or alternatively, “Even if there were copies being made, this is fair use.” So there's a fair use component here.

Another argument along the fair-use line is, “Hey, look, this is no different than us going out into the world and being influenced by things that we look at and see and hear, and then replicating them. It’s no different than creating a song that's influenced by all those songs I sat in the cafe and listened to. You can be influenced by something.”

So the argument is, I could sit down and study every single song by an artist in extreme detail. I could map out what all the keys were, the BPMs, the lyrical content, all that stuff. And then I could use that information to write songs that are super similar to that person, correct?

Yes.

Under the hood, it’s just feeding information into a computer, and through machine learning at a scale that no human can do, it’s figuring out how this thing is actually built. What are the connections? What are all the variables?

That's exactly right. There's a rhetorical question I've been asking, and I really have not heard a great answer yet. Why are we so quick to find liability for doing something at scale with machines that we would otherwise find to be completely and utterly normal and fair use when done individually across thousands and millions of humans? What is it here?

A great colleague of mine retorted at one point, “Well, it's like walking past your neighbor's flower bed and wanting to pick one flower. You don't do that because if everybody in the neighborhood came along and started picking the flowers, there would be no flower bush left for that neighbor to enjoy, and it's their right to prevent you from using that.”

I don't know if I buy that argument. A better analogy might be, “You’ve taken my flowers seeds, grew your own flowers, and now my flowers are competing with your flowers for customers.” Again, I think there's some validity to it, but we have to dig around that.

And then there's the second argument that says on the output, these are derivative works, and that's a really key term that's spelled out in the Copyright Act and specifically reserved for the author/owner of the original works. But then we get into complicated issues around de minimis use and market substitutes.

The other question too is which works are we referring to when we say derivative works?

Drake has hundreds of songs in his catalog that are all owned in different capacities by different people, with different songwriters, different collaborators, and different labels.

So like this AI Drake track is a derivative of which one of his works exactly?

You're absolutely right. You hit the nail on the head because then it becomes an identification problem.

But my same buddy said the other day, “That's not our problem. It's not our problem to figure out which music you stole. It is incumbent upon you before you make these copies and just use it to create derivative works under the Copyright Act to figure out a way to pay and compensate the people that you're taking from. And by the way, we should be able to prevent you from doing that too”.

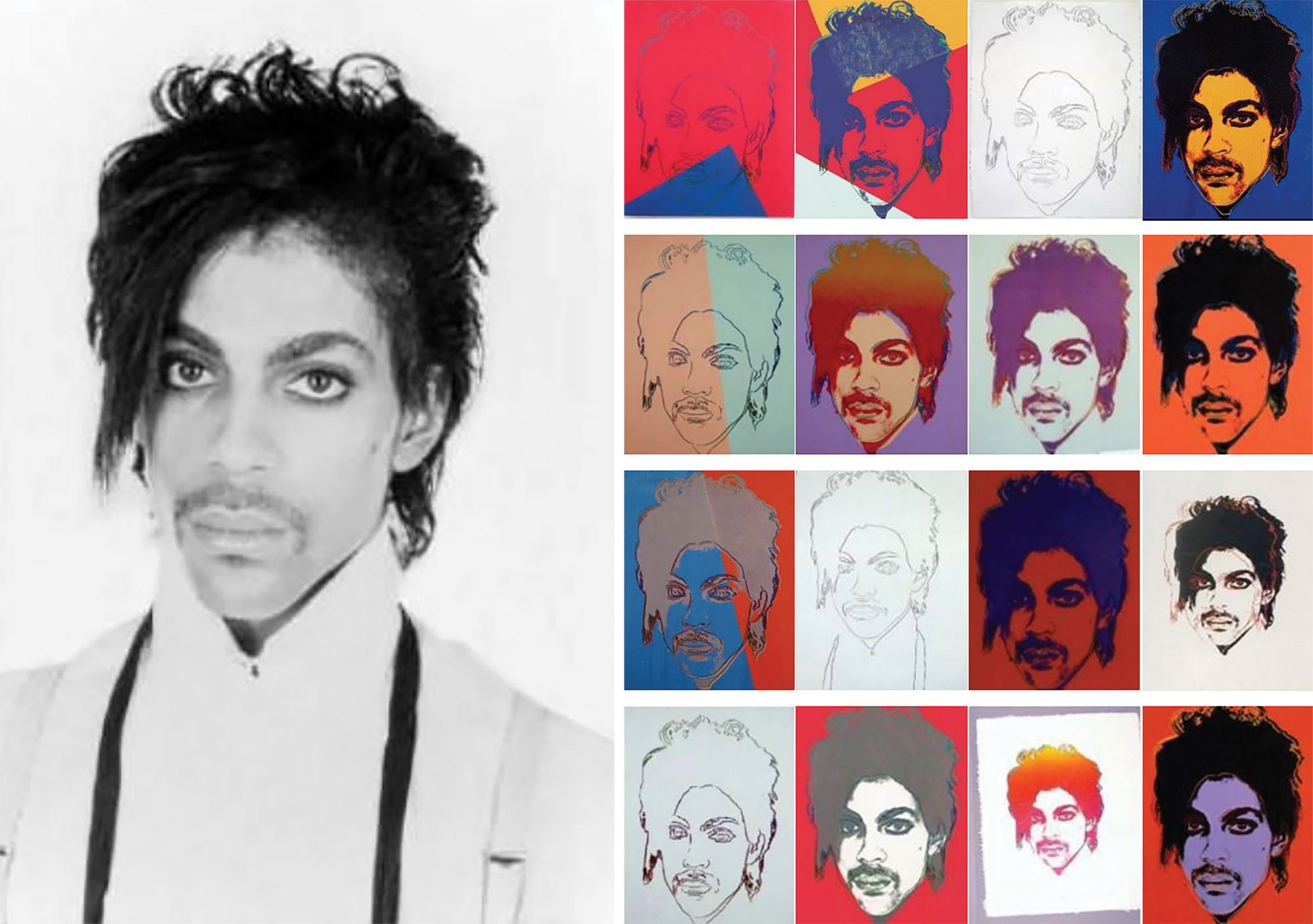

So fair use at the moment is extremely hot in the courts. There's a couple cases in front of the Supreme Court, the Warhol one and the Jack Daniels one,

[Editor's Note: The Supreme Court has delivered verdicts on both the Warhol and the Jack Daniels cases in the time since this interview was conducted.]

This leads me to this saying I've been coming back to lately, which is to say that “a theft from one creator is a tragedy, but a theft from millions of creators is a transformation.”

And it reminds me of what Spotify did. It reminds me what a lot of these too-big-to-fail people did. They use a 'move fast, break things, ask for permission later' model. And they became so big that rights holders had no choice but to sort of negotiate with them after the fact. I think that's a lot of what's happening right now.

I mean, I definitely appreciate a lot of the academic arguments about de minimism the fair use side of things, but the problem is that these systems are not perfect at hiding source content. Sort of like what we see in the Getty images case where they showed actual examples where the Stability AI model reproduced images that are substantially similar and even include the Getty watermark.

But isn't the crux of that case that they're using the Getty watermark in the new images? That’s a big part of the argument, right? Had they not included the watermark, the arguments would probably be very different.

So here's the thing. There's two main issues at play: one being copyright-based and the other being trademark-based. One the copyright side, there's a provision of the Copyright Act that makes it illegal to remove copyright management information without explicit permission from the rights holder. So Getty is accusing Stability AI of removing watermarks and metadata associated with the images. That is, scrubbing the copyright management information.

But then further, Getty is saying, “Not only are you scrubbing the metadata and the images of the watermark identification when you're ingesting them–that bit in itself is a violation of the Copyright Act–but then, to the extent you're actually outputting the watermark, that's a trademark violation because you're reproducing and diluting our brand with your egregious outputs.” What they’re saying is like, “We didn't take this bad picture. It's disparaging of our name. It's making us look bad,” so forth and so on.

So again, it's a very nuanced thing that's going on right now and there's arguments on all sides.

Interesting.

Yeah. So that leads us up to the right of publicity.

Because there are situations where a person could have access to a tool that they did not create. They're not part of the conversation about inputs, "Did you steal anything to create your model?" All they have is an LLM of Drake's voice, right? So now the question becomes, "What, if anything, can they legally do with Drake's voice?"

There are two different situations here: one in which you do a cover version, like Drake's voice doing "Juicy" by Biggie, right? And then you have a second situation where you sit down and write a whole new record front-to-back, but you're using the sound of Drake's voice to recite new melody and lyrics.

So in the first instance, it's a cover version. Insofar as you are not incorporating pre-existing sound recordings, there's really probably not a copyright infringement claim in that because you have the compulsory mechanical [license] to lean back on to do cover versions.

But is it violation of the artist’s right of publicity (i.e. their vocal likeness)? What if you use Drake’s name in the title? Is that a trademark violation? What if you specifically said, "AI cover" in the title? This is where it gets a bit more sticky.

And, this is important. There's a specific exemption, a carve-out for soundalikes in the copyright law. And it simply says, “It doesn't matter how close a cover version sounds like to the original as far as copyright law is concerned."

It makes sense that it wouldn't be protectable because we may naturally be born with voices that sound like other people.

However, the issue gets stickier when that cover or soundalike is purposefully designed to trade off the goodwill of the original artist, particularly in the advertising (i.e. commercial) context. That goodwill and commercialism implicates a person’s right of publicity.

But we'll get into that in a second because the difference between an expressive work and a commercial work in this context is important.

So back to the cover version. You have the compulsory mechanical [license] to recreate the sound recording, i.e. your own version. Like I'm just some dude on the internet that grabbed the AI voice emulator and now all of a sudden I wrote a new Drake song. I put it out. So there's that situation.

But then we get to the other situation in which the composition is totally original and you’re not relying on anybody’s prior work. You don't even need the compulsory mechanical license because you’re not recreating a previously-released song.

So let's go back to the very easy case where it's all original except for the artist's voice. Here we’re running into issues around right of publicity. The problem is, the right of publicity is currently adjudicated under state law.

Remember when we mentioned the carve-out for soundalikes under copyright law? Well, there's something called federal preemption, which basically says that a state law must yield to a federal law when directly in conflict with that state law. The right of publicity is listed under state law whereas, the Copyright Act (i.e. the one that says that you can absolutely do soundalikes) is federal.

So in the cover version scenario, you can argue that even if you are using Drake’s vocal likeness and create a soundalike without his permission, there would be no liability because you would be preempted by the Copyright Act.

But there’s a catch. And that is, the use can’t be for advertising or selling goods or services. The two leading cases that address commercial use of a celebrity soundalike are the Bette Midler case, and I think Tom Waits was the other one.

In the Bette Midler case, Ford [Motors] entered into talks with Midler to record a

song for their commercial that ultimately fell through. So instead, they hired a person that sounded near-identical to Midler to record the song, and Midler sued. The Court found that, because Ford’s use was primarily motivated by, and in association with, the commercial sale of vehicles, it was commercial (rather than expressive) speech that implicated Midler’s right of publicity and was not preempted by the Copyright Act.

So it was less about copyright and an expressive work than it was about the association of her in the sale of Ford trucks, which begs a question that I still struggle with to this day. At what point does releasing and monetizing the performance of music become a commercial use? Or is it primarily expressive and the monetization is a secondary, incidental byproduct of the artistic expression?

The original 1986 ad that Bette Midler sued Ford Motors over in 1988.

So if I make a soundalike song and I sell it, in some way that's a commercial good, but there's also an expressive component to it, so that would be okay?

But if I'm Ford or a retailer or whatever, and I think, "Well, you know what, I can go use one of these generative tools and get something that sounds like a big artist," that's not okay because the primary intent is not to express yourself. It’s to use it to sell your product.

Even though in the first case, you know, as an artist, you're still selling your music. The view would be that the primary reason for creation is expression. Is that right?

Yeah, because think about it. The right of publicity is primarily concerned with the exploitation of a person's name, image and likeness in association with sales. But I agree with you, at what point does music become commercial, right?

And this is the Warhol case right now. Going back to the point about AI labels, if somebody is starting a label that is meant to release music that is 100% created through generative AI, there's probably not a lot of expression there, you know. Its primary use is for commercial purposes.

I mean, again, this is where the human side of judging comes in, which is like, where does it go from being expressive to commercial? What is that line? It's not clear. And I think that's why it always ends up at a jury because you've got to get through the fair use factors and look at them.

And one of them, the fourth fair use factor, considers the effect on the market for licensing that particular piece of creative work and the derivatives thereof. And so it is interesting, right? Because if they're using Drake to supplant Drake, that's a fucking cold move.

But back to the right of publicity. The question then becomes, okay, what if it's not in association with commercial goods? What if it's just literally artistic? You're putting it on YouTube to show, “Yo, check out this new AI bop, this is great.” That's a real question right now for a lot of people.

I'm not all that confident that it's actionable in that context based solely on the statutes as they are meant to be read right now. So if you're just a kid throwing up, an original song using a voice emulator, and we all know it's supposed to be Drake, we all know it's Kanye, that's an interesting conundrum. I just don't see the legal argument right now. And I think a lot of attorneys sort of feel the same.

Ok so we've talked about copyright. We've talked about right of publicity. What about the trademark side of things?

So Drake™ is actually a business name for Aubrey Graham. Like Drake is a trade name, it's a business name. Take any other number of bands, they're all fictitious names for the most part. So the question then is, is that the final buttress there is?

Like, okay, look, “You're now diluting my brand by using it in association with this fucking terrible AI record that I hate and you're calling it Drake.”

That I think is a pretty strong claim.

But the contention, again, comes back to the Rogers Test, which says that using another's trademark in an artistic work would be accepted under fair use, provided that the expression (i.e. the art) has (1) some artistic merit and (2) is not explicitly misleading.

So if a kid on YouTube is just like, “Yo, this is Drake, buutttt ... Oh, here's the disclaimer. It's not really Drake. This is AI. I just think this is a cool record and I always wanted to hear Drake cover Biggie’s Juicy." Is that misleading?

But now here's the problem. That kid then goes to put it on Spotify where that disclaimer is not available. How do you incorporate Drake's name without consumer confusion? And is that in association with the sale of "goods" or "products"?

That's always been the question for me. Like where is that line? Because there is this point at which an “artist” passing off as an artist can use expressiveness as a front to just make money.

So yeah, man. You can see the fucking stew of legal machinations here, right?

We're starting all the way back from crawling publicly available websites to ingest and learn from, and take the factual information out of it. BPM, all that other shit, transforms that into something new that then allows you to output something completely new. So there's that.

Then there's the output. What if it's modestly similar to something that went into the input? How about substantially similar? Is it a derivative work? When we’re talking training on millions and millions of works, how do you even prove that? Is it infringing?

Then, we add all the right of publicity issues on top of it, as well as the talk about the association with commercial goods. We have to differentiate between both federal and state law, copyright versus the right of publicity. And then there is this differentiating factor where we need to consider whether or not it's in association with goods and services in a commercial setting. So many angles and issues to consider.

I don't know. I don't think anybody knows at the moment. And then you got to jump from there to trademark, right? And then figure out what's going on over there.

I mean, one thing we didn't touch on that I've been wondering about is how does publishing fit into all this? I don't even know where to start with that question, to be honest. Do you have any thoughts on that?

So it's a different consideration for sure. Because if I'm a publisher, I'm kind of loving this. Like I want this to happen.

As a matter of fact, I saw an article the other day about Primary Wave, or it might have been Hipgnosis. Regardless, when you have all this money that came in the last 5-6 years and bought up all these catalogs, they want their return on investment. And so we've got to get these songs out there. We've got to get licenses going. The article that was very provocative. It basically said like, "This is good for publishing because publishers are going to get paid on all these new AI cover versions." It's just like cover versions en masse.

But the issue there to be determined is precisely how the PROs, Congress, and other stakeholders are going to approach licensing AI works. It’s still TBD, but all I can say is that if-and-when they manage to put such a system in place, somebody is going to be very happy with all those pennies adding up.

Do we need a new sort of royalty mechanism to cover these kinds of usages at the national level?

It's a great question. If we break that down, right, what would be the royalty? Like what would be the basis of the law? What we're saying is, “Because we can't stop this, we are going to capture it and put a licensing regime around it,” so it gives people compulsory carte blanche permission to do this stuff.

But the people who ultimately play and feed the music to the public still have to pay a public performance royalty and a mechanical one. I’m not sure what a new royalty mechanism would add that the preexisting stuff doesn't already cover, unless it was a blanket compulsory license to use the vocal imagery.

But without a technical solution, how do we ever enforce a new right to use somebody's voice? I don't think it's illegal to say “I'm inspired by __, I want to write a song by __ that sounds like __” And so why would it be illegal if we do that in a machine?

I mean, you can do that stuff already, right? You can go on YouTube and watch a tutorial for How to make a beat that sounds like Skrillex.

And if you're a decent producer, who has the technical chops to make it sound similar enough, no one could tell the difference.

Yeah 100%. I don't have a great answer for that, but I do agree that we need a holistic approach to this. Both from an AI perspective and also, by the way, as a blockchain thing, because I think that's part of the bear.

Yeah. We definitely need a mechanism for verifying authenticity.

But then the other problem as it relates to verification through blockchain, does this suddenly mean the artist is responsible for approving every single upload? Do they need to approve a feature only released in China? An Australian-exclusive remix?

Actually I think the answer is the opposite. Nothing can be tagged unless it has been pre-approved. Like the artist is in control of clearing the use.

Instead of giving the green light on individual tracks, they would giving the green light to this record label, and then they can upload whatever they want.

Because I agree, it's onerous. It starts from the other direction, which says, “Okay, this is my ongoing running list, verified on the blockchain, of collaborations, creative works, or projects I've been associated with. And if it doesn't match up, if the hashes don't match, it's not me.”

Look, I don't think it'll ever be fully automated, because that's just not how collaboration works, but closer to creation, we can get the metadata captured. If you can create a hash immediately after the session, assign it to the rights holders or the creators right there, and then it travels with that piece of audio, and somehow, it logs the information as it goes down the creative pipeline.

Yeah. It almost needs to happen inside of Ableton or something.

Exactly. There are people working on that. I know that for a fact.

So before we wrap up, one thing that comes to mind is this idea that the music industry might become Hollywood, where it's just reboots forever.

Will we just keep listening to the same artists over and over and over again? Or is this going to give new artists so much more creativity that they'll still be able to establish their own lane? Is it both?

Yeah, as we said, I don't think they're mutually exclusive at all. I think it actually presents an incredible opportunity for estates of deceased artists to reinvigorate their personality. And not just rely on back catalog, but really be inventive going forward.

I heard an AI cover version of McCartney the other day. It was beautiful. And I was like, "this is cool. I know it didn't happen in real life, but I'm putting it in that box." It doesn't have quite the value that a real version would have for me, but I know that going into it.

At the same time, there's no way 13 or 15 year old kids are just going to listen to The Beatles for the next hundred years. They've always rebelled against their parents. So I think savvy estates and legacy catalog holders will find a way to do cool new shit and keep it fresh.

From a cultural perspective, 100% AI is going to create new genres and new artists and superstars in their own right. It's whether we ascribe the merit to them, though. Like we generally accept that spinach, sweet potatoes, and brown rice are better for us than Kraft Macaroni out of a box. These are universal truisms, and the closer to the whole foods and vegetables of music we stay, the healthier we are.

But every now and then, you know, there’s a mental health element to enjoying some Skittles and ice cream and all that stuff too.